Want to be a data journalist? Learn these important tools

As

the world of journalism changes many journalists are looking to learn

new skills; skills better suited to an industry that is increasingly

digitised and visual. For many that probably entails learning something

about data journalism and visualisation. But, if you’re from a strictly

printed words background, the change can be daunting.

For

a start there is an ever-growing list of data journalism tools that are

available which can be daunting. The question becomes, where to start?

There

is no single right answer. What you need to do is to decide what it is

you want to achieve, and your particular working circumstances. If you

work in a newsroom and your primary output is in a newspaper then you

probably don’t need to learn to make interactive graphics. But if you

work online then you may want to learn some data visualisation tools.

The

important thing to understand here is that no matter what kind of

journalism you do you can benefit by learning some basic data journalism

techniques. And don’t be fooled by the all-to-often portrayal of data

journalists as code hackers. There is a place for great programmers but

you don’t have to be a programmer to be a data journalist.

What

follows is an opinionated list of tools worth taking the time to

explore. Most of these are tools I have come to rely on for a range of

different projects, such as data driven stories like this. This is not a comprehensive list of tools, just a shortlist that makes up a good toolbox.

Part 1: The data journalism basics

Spreadsheets

Yes,

you can’t escape it. Spreadsheets are the core tool for any data

journalism project. Too often journalists fall back on the old pretense

that they’re no good with maths. You don’t need a PhD in mathematics to

use a spreadsheet but a basic understanding of averages, means, medians

and the ability to work with a spreadsheet will boost your reporting

skills. If you’re completely new to spreadsheets there are many tutorials online that will have you up and running in no time.

For

most people the first thing they think of when they hear spreadsheets

is Excel, which is a great option but by no means the only one. Google Sheets

is preferred by many spreadsheet newcomers because its simplified set

of options give them the bits they need without the huge array of

functions in Excel. If you want something free but powerful, Libre Office spreadsheets is one of the best options.

Document organisation and collaboration

One of the challenges in doing data journalism is how to manage large numbers of documents without losing your way. Again, Google Drive

is a good starting point. Drive stores all of your documents in the

cloud and makes it easy to share these easily with other users. Drive

also has built in version tracking, although it’s not immediately

obvious, which means you can go back to previous versions of a document

if you end up in a data dead end or if you make a mistake.

While Drive has a ton of uses, sometimes you need something a little more focused on the task at hand. Which is where Document Cloud

comes in. Document Cloud is also an online document storage service but

it has a number of features that make it a great tool for data

journalism. One of the most useful of these is the ability to upload

PDFs to Document Cloud and have it convert these to text for you. Not

only that but Document Cloud also indexes documents and over time it

becomes possible to search across all your stored documents for

particular words or names. Document Cloud includes annotations, it can

build timelines from documents and makes it easy to embed portions of

documents into your online stories. Also, multiple users can collaborate

on the documents. Your newsroom will need to apply for an account but

the service itself is free for news organisations.

If you’re looking for something a little different to Document Cloud or Google Drive then it’s worth taking a look at Git and Github.

Git has largely been the domain of programmers but increasingly

journalists and other writers are turning to Git/hub for a range of

reasons. Git is a version control system. You can create files, edit

those while being able to revert to previous versions at any point. You

can also “branch” files which means creating a second or third version

of your files which you can experiment with. If these experiments work

out you can then “merge” the changes back into your main files. If not

you can dump the experiment and switch back to your original files. If

you’re keen to try out Git and Github then do yourself a favour and

watch Daniel Shiffman’s entertaining Git and Github for Poets YouTube series.

Collecting and cleaning data

The

other reality about data journalism is that it is a rare occasion when

you get to deal with clean data. Either you’ll be dealing with dozens of

PDF files that need to be converted into something useful and verified.

Or you’ll have a dump of messy CSV or excel files.

If

you’re looking to convert PDFs into text/numbers there are dozens of

good tools that do good to excellent conversions. The problem is that

PDFs are tricky things and your success converting them is largely based

on how they are created. PDFs that were created directly from

spreadsheets are typically easier to convert than PDFs that are actually

made by scanning in a document and then saving to to PDF. More often

than not you’ll deal with this latter type, especially if you’re getting

leaked data.

If

you’ve got a Document Cloud account this should be your first stop

because it has PDF conversion built in. If you’re looking to convert

just a portion of a PDF, or multiple similar portions of a document then

try Tabula.

With a little bit of practice Tabula can be made to do pretty reliable

PDF conversions, even if your data is spread throughout multiple

documents.

There are also a number of online PDF conversion tools that work with varying degrees of success. One of the more popular is CometDocs which does conversion to multiple file formats. Zamzar

offers a similar service. If you’re looking for something a little more

robust then Nitro is worth testing. Nitro offers a free online PDF conversion service

but it is also available as a paid-for desktop application. It’s not

cheap but it’s very capable if you’re dealing with multiple documents on

a regular basis.

Once

you’ve got your data probably need to clean it. If the data is not too

messy or detailed then a spreadsheet is a good starting place. But, if

you’ve got a file with hundreds or thousands of rows and multiple

problems then Open Refine

is the tool of choice. Open Refine used to be called Google Refine and

it makes it relatively easy clean up dirty datasets. One of its

strengths is its ability to work with just portions of your dataset at

time. For my money, if you’re going to commit to learn anything then

Refine would my choice. Once you’re over the initial learning curve and

you discover the power of Refine you won’t look back and there are some good introductory tutorials available for Open Refine.

A tool similar to Open Refine is Data Wrangler

which aims to make it as easy as possible to clean up and manipulate

large data sets. I’m not overly familiar with Data Wrangler so my

preference is for Open Refine but I mention it because it looks to be a

promising tool.

Part 2: Analysing and visualising data

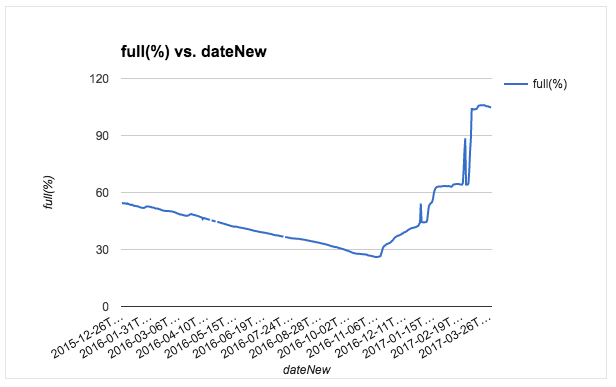

Once

you’ve got your data cleaned and sorted you’ll want to see what the

data is telling you. If you’ve read anything about data journalism

you’ve probably heard someone say that you need to interview your data

like you would interview a source. Just because you’ve got a set of data

doesn’t mean you have a story. What you need to do is look at the data

in multiple different ways to see what stands out. Also, when you do

this you might well spot anomalies in the data, a sudden spike or dip in

values. Sometimes these are the stories but often these are the result

of a problem in your data.

One

of the easiest tools for doing a quick visualisation or two is Google

Sheets. Exel or Libre Office could also be used but Google Sheets is

perhaps the easiest of the tools when you’re looking for a quick chart.

It’s worth looking at your data in multiple different views to see what

the patterns look like.

Another way to do initial visualisation is with one of a number of online tools. One of the easiest to use is Datawrapper

which outputs your charts in multiple different ways. It’s a useful way

to switch between different views quickly to get a sense of what works

well. There are a few other services online, such as RAW or Quartz’s Atlas charts which produce good results.

Once

you’ve got an idea of what you want to do then it’s time to start

creating. Most of the programs mentioned above will produce embeddable

versions of the charts you’ve made but they may be limited in adding

other elements like images, text areas or extra labels. For that you’ll

need to look at some other tools.

ogram

are among the best and easiest at doing this. Both make it easy to

combine charts with other visual elements, and if you start with one of

the pre-built templates you’ll have something decent looking in next to

no time.

If you’re looking for something more detailed with more than just a few default chart types then you should probably try out Tableau Public

which is free and extremely powerful. It can build everything from the

simplest charts to complete interlinked dashboards. But be warned, the

initial learning curve can be a little daunting for first-timers. If

you’re serious about data visualisation then take the time to learn more

about Tableau Public. But if you just want the occasional chart to

dress up a story then stick with one of the other options.

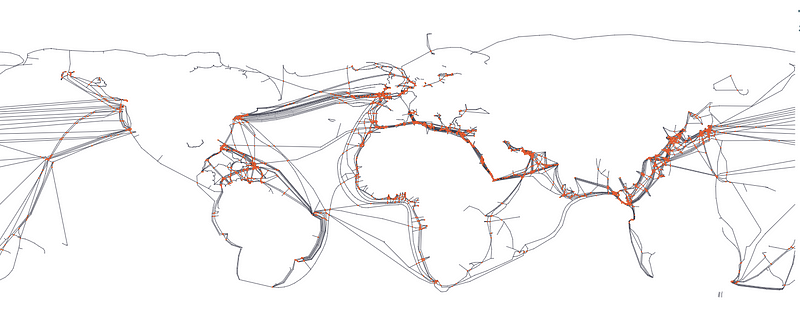

Part 3: Maps and mapping

If

you do any kind of data journalism you’re bound to come across

geographic data. Which brings up the issue of mapping tools, some of

which are simple point and click affairs while others border on the

arcane. So you need to think carefully about what you’re trying to

achieve with geographic data.

Too often the first instinct is to plot the points on a map. Which is worth doing in the initial exploratory stages in almost all cases, but often a map is not the best way to illustrate the point of a story. For example, having a map with 200 points all clustered around a small area is often not the most informative way to display data. While shaded contiguous areas to indicate some sort of distribution can be far more effective.

Having said that, a good map done right can add huge amounts to a data story, so what are the best tools?

Once again Google is a good starting point. Google My Maps

is one of the simplest tools to use. It’s pretty intuitive to use and

makes it easy to look up geographic points, draw lines and shape on maps

and even add driving directions. If you just want to illustrate where

or how something happened geographically then there is no better place

to start.

A step up from My Maps is Google Fusion Tables.

This is also part of the Google Drive suite of tools. Fusion Tables in

fact does a lot more than just make maps, though that is one of its

strengths.

Fusion Tables also make it easy to filter data sets, do some cleaning up of data, merge multiple datasets into one and a fair amount more. It’s a little tricky at first but is a good choice when you’re dealing with larger data sets.

Fusion Tables also make it easy to filter data sets, do some cleaning up of data, merge multiple datasets into one and a fair amount more. It’s a little tricky at first but is a good choice when you’re dealing with larger data sets.

If you’re really getting into this mapping thing and you want a bit more than the previous two options then CartoDB

is your next step. Carto is all about maps and it has the potential to

make excellent maps with multiple layers and different designs so long

as you’re prepared to put in a little initial work. Personally I find

Carto an excellent choice for mocking up a quick sample map or merging

sets of data to include geographic points. It makes it pretty simple to

visualise larger sets of data and make decisions about where you should

go with your project. Carto also makes it easy to export the cleaned and

fixed datasets into many formats which makes it easy to use in other

applications.

There

are literally dozens of other applications for making maps some of

which are extremely powerful but often also very complex. ArcGIS is popular tool, as is the open source QGIS

application but both are aimed at fairly experienced mappers so the

learning curve can be steep. If you’re keen to try your hand at making

your own map styles then Mapbox is great for that. Mapshaper.org

is another of my most commonly used maps tools because it makes it easy

to get a quick visual representation of the data in your map files and

it also makes it easy to simplify map shapes, something that can be

extremely useful in keeping download times down.

In conclusion

Data

journalism is a broad area of work with place for many different

skills. Some might favour the visualisation side of data journalism

while others may prefer the mapping side. No matter what you prefer

doing or what the limitations of your newsroom are there is always

something more to be learned about data journalism. The recommended

route would be to start with the basics above and then gradually move

into some of the more detailed areas.

From

experience the best way to learn to become better at data journalism is

to practice. Find a real world dataset and see what you can make out of

it. It’s only when you’re working in a real world scenario that you’ll

really learn the ins and out of good data analysis.

Comments, thoughts, feedback? Leave a comment or find me on Twitter. Please recommend this article if you found it useful.

This article was originally posted on Media Hack.

Sign up for my Media Picks newsletter. It’s a weekly roundup of journalism developments, tips and tools.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.